Gaining entry to the Royal Yacht Squadron clubhouse, on the Isle of Wight, can be as difficult as opening a Colchester oyster, writes Philip Rathgen.

For the last 200 years, its members have maintained a strict tradition of keeping themselves to themselves. Only on very rare occasions do the wrought-iron gates of Cowes Castle swing open to admit outsiders - such as when watchmaker Panerai hosted a dinner in the clubroom of the Squadron, during this year’s Panerai Classic Yacht Challenge.

Since 1855, the yacht club (founded forty years earlier in London) has been based in the castle which is a prominent feature by the harbour entrance at Cowes on the Isle of Wight. Behind these walls, which Henry VIII had built to defend the harbour from the French navy, 330 stalwart yachtsmen uphold the values of the British Empire against the rising tide that is the modern world. To be admitted to this select club is a social accolade. However, the qualifying procedure follows strict guidelines and, more often than not, results in a polite but firm refusal, no matter how rich or powerful the hopeful applicant.

This elitism is derived in no small part from the fact that in 1851 the Royal Yacht Squadron inaugurated the famous America’s Cup trophy, when it invited the New York Yacht Club to produce a challenger to its own fastest yacht. The NYYC despatched the ‘America’, which won the race and gave its name to the new trophy, originally named the 100 Sovereign Cup. And so the America’s Cup was born.

As part of last month’s Panerai Classic Yacht Challenge, where classic sailing yachts compete on The Solent (the stretch of water between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight), the Admiral of the Squadron - for the first time ever - invited non-members (and even ladies) to dine in the Members Room. Only correctly attired (dark suit and tie) guests with personal invitations are allowed past the careful scrutiny of the security staff. The use of a mobile phone or camera is frowned upon. Once through the gate, though, it’s time-travelling back through 150 years of history.

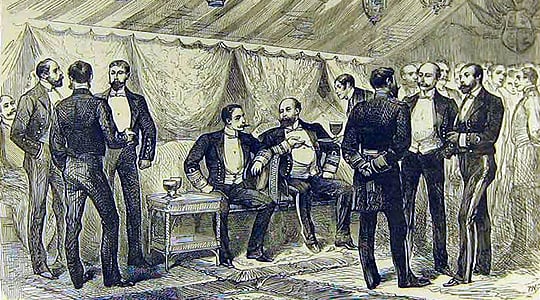

The clubhouse was designed in the Victorian style and is exactly how anyone would imagine the quintessential English club: gentle pastel colours for the walls and floors, and furniture that might be on loan from an ancestral home. The many oil paintings – usually quite large – depict either scenes of naval battles or portraits of former worthy members of the Royal Squadron. After some socialising, the club’s butler smartly raps a silver hammer, declaring “dinner is served!” and bidding everybody into the Members Room. Impressive trophies, brought home by triumphant club members from regattas across the world, adorn the formally laid table. There then follows a four-course meal, with each course announced by the Master of Ceremonies. At some point, between the bouillabaisse and the fillet of veal, you begin to wonder at conversations that might have taken place in this exclusive room. After all, crowned heads – including even the German emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II and his yacht Meteor – plus many statesmen were members of that select circle in the Squadron. In keeping with the tone of past glories, a glass of port is served at the end of the meal.

Originally, only the owners of yachts displacing at least ten tons were eligible to become members of the Royal Yacht Squadron. This rule was changed to ‘gentlemen actively interested in yachting’, when lightweight construction became more commonplace. Traditionally, the members of the Squadron are the only civilian yachtsmen permitted to fly the colours of the Royal Navy. And neither wealth nor power was enough to gain admittance to this exclusive society. Despite meeting all the pre-conditions for entry, the Scottish tea merchant and unsuccessful America´s Cup contender, Sir Thomas Lipton, had to wait until his 80th birthday before his membership request was finally granted. After that, he had little time left to take part actively in the Squadron's life – as he died two years later.

In the 1970s, the rejection of the successful yachtsman and British prime minister, Edward Heath, caused quite a stir, subjecting the elite club to much adverse publicity.

As the waiters begin to clear the tables – sterling silver salt and pepper shakers whisked away first, just in case the guests fancy a spot of thieving – it is made quite clear that non-members have nearly outstayed their welcome. Leaving the premises, one notices a small opening in the wall. The ‘servants’ fund’ prompts homeward-bound members to leave a tip in appreciation of the attention and care lavished by the club’s staff. There is a story about a former club member who had an unfortunate experience with this. On making his way out, the unfortunate gentleman slipped only a few coins in the slot, rather than the customary folded notes. Deemed an act of disrespect, he was swiftly expelled from the Squadron.

Given the choice, members would want everything to remain ‘ship shape’ for the next 200 years. But 21st Century reality is catching up with them faster than they would like. As this sponsored dinner proves, even this venerable organisation is not immune to the lure of modern marketing strategies. Of course the RYS values Panerai’s commitment to the Classic Yacht Challenge, and hasn’t simply succumbed to filthy lucre from ‘trade’. Let’s hope so, anyway.

Text: J. Philip Rathgen

Photos: JPR / RYS

ClassicInside - The Classic Driver Newsletter

Free Subscription!