Text: Tony Dron

Photos: Porsche Press

Talking of Porsche cars, how many people today casually roll out the name 'Carrera' without knowing what it really means? Carrera, the Spanish for 'race', has been used by Porsche for the best part of half a century, and it first appeared on road cars in 1956.

The Stuttgart company adopted it in honour of a brilliant success in the 1954 Carrera Panamericana, the gruelling road race which ran the length of Mexico from 1949 to 1954, at first from North to South but after that in the opposite direction, taking in over 1,900 racing miles (3,058km) from the Guatemalan border to that of the USA. And this was one hell of an event, without question the world's longest and most dangerous true road race.

Starting at Tuxtla Gutierrez, the first third of the race took in mountain roads, some as high as 6,000ft(1,829m) with perilous drops. The course was divided into sections, tackled on five successive days. Much of the last half of the race was on near level ground, incredibly fast with some straights up to 50miles(80km) long - simple highways but mostly with fairly good tarmac. Run in November, it took in steamy tropical heat near the start to sometimes bitter cold at the finish at Ciudad Juarez, on the Texas border.

The Mexicans ran the race with military precision, with over 25,000 police and troops deployed to keep the roads clear. A man was stationed every 100yards(91m) along the route: if any unauthorised person got in the way, the men had orders to shout a warning and then open fire. There were no reports of any shooting, but the Carrera claimed several lives from accidents. In 1954 alone, eight people were killed.

There were countless miraculous escapes. Carroll Shelby, later the world-famous father of the AC Cobra, was a young driver in an Austin-Healey 100S on the 1954 Carrera. Running wide at high speed on a righthander, he side-swiped a large boulder and piled into a rock outcrop. Shelby escaped with a bad shaking and broken arm but the car was a total wreck.

Entering such an event as a works team was then a serious undertaking for Porsche, still a very small concern which had produced its own first prototype only in 1948. Led by Dr Porsche's son, Ferry, progress was rapid and sure: he and his team knew that conspicuous competition success was vital to the development of engineering and sales.

Porsche was not then in a position to challenge for outright victory, but class wins at the Nurburgring, Le Mans and in top European rallies soon brought wealthy customers into the Porsche fold. To expand beyond Europe, there was no better showcase than the great Mexican Carrera: people in North and Central America bought new cars on the strength of the results. By 1954, Porsche had a little 1500cc sports-racing car that was capable of really astonishing performance in such an event.

But we are jumping ahead: 1954 was far from the first time that Porsche cars had competed in the Carrera Panamericana. Two private entrants had entered the 1952 event, the third race in the series, in brand new road cars; and one of them, a cabriolet driven by Prince Metternich, finished a remarkable 8th in the sports car class.

The motorsports boss of Porsche in those days was Huschke von Hanstein, 'The Racing Baron': always alert to important opportunities, von Hanstein put together a strong team for the 1953 Carrera Panamericana. He had two great drivers, rising star Hans Herrmann and established ace, Karl Kling, outright winner for Mercedes-Benz the previous year.

They were to drive the latest Porsche 550 Spyders, purpose-built sports-racing cars with tubular ladder-type chassis and lightweight aluminium bodies. Unlike the rear-engined road cars, these 550s had mid-mounted engines but they were then still near-standard 1.5-litre pushrod types, producing 79bhp on regular petrol. Top speed was about 125mph (200kph) and weight only about 550kg.

They shipped the cars to New York, ready to trail them thousands of miles South, taking in some relatively minor US events on the way to please the importers. Ever the innovator, von Hanstein picked up the American way of thinking immediately, securing sponsorship from Telefunken Radio and from a Porsche client in California, Fletcher Aviation.

In the US, things got off to a tricky start when Kling was arrested by immigration officials on arrival, thanks to a paperwork error. By all accounts, Kling had spent the Second World War as a Daimler-Benz engineer but his name was mistakenly placed on a list of wanted former Nazis. He was apparently not that pleased to spend his first weekend in the States as a detainee on Ellis Island.

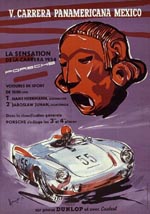

In the big race, however, things got worse: Herrmann crashed out, probably as an instant result of steering damage, and Kling's car broke down. Porsche's honour then lay with the privateers. By sheer reliability, they did not let the factory down. An exiled Czech and one-time Guatemalan Porsche distributor, Jaroslav Juhan, now led the class in a 550 Spyder that had completed the Le Mans 24hrs. Later he too broke down, leaving a Borgward in front by two hours, 30 minutes. But the Borgward also gave trouble and in the end only two cars finished in this class, both of them private Porsches. The class-winning driver was Jose Herrarte of Guatemala, at 79.9mph. Five people had been killed in the race, including the popular Ferrari driver, Felice Bonetto.

As ever, Porsche had learnt much, and fast. In 1954 they returned for a race that was tougher than ever. The rules had been tightened, allowing only one hour's servicing after each stage. That was tough enough, but the previously reasonable roads had been hastily repaired after damage by recent floods and landslides.

The 1500 sports car class drew 13 entries, the Porsches facing mainly Borgward and OSCA opposition. But Porsche now had an engine to match a developed version of the 550 sports-racer, which included much-improved rear suspension. The new engine was Dr Fuhrmann's legendary but complex four-cam flat four which he later dismissed with a smile as 'a folly of youth'. Yet, with its super-short stroke, big valves and ingenious detail, it was in truth an early masterpiece which did wonders for Porsche's results and reputation. Developing a claimed 117bhp at 7,800rpm from 1,498cc , it gave real racing performance.

Under von Hanstein's management, Hans Herrmann returned to Mexico with one of these cars in 1954. Local man, Juhan, was upgraded to an even newer 550 in time for the race. From the start, Juhan was cheekily mixing it with some of the bigger Ferraris, but Herrmann was held back by a misfire and at the end of the stage, Bechem's Borgward was lying in an incredible third overall. Bechem crashed on the third stage and was hit by a Pegaso which burst into flames. Meanwhile Juhan diced successfully with an OSCA as Herrmann made up ground fast from his low position. Going into the lightning fast final stage, Herrmann needed to catch Juhan to win the class: the Porsches were flying.

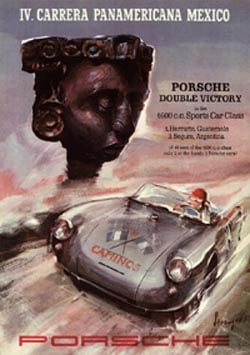

Maglioli's big Ferrari flashed over the line at 134mph, just ahead of Phil Hill's slightly slower Ferrari. Minutes later, the glorious Porsches staged a flat out side by side finish: not only had Herrmann and Juhan finished first and second in class, they had taken a remarkable 3rd and 4th overall. Herrmann's class-winning average speed for the 1,908 miles was 97.63mph (157.12kph).

A Porsche legend had been created.