In a world of under-the-radar private treaty sales, ultra-exclusive concours d’elegance events, and non-stop continent hopping, it’s rare that you get a chance to break bread with one of the classic car industry’s true heavyweights. The nephew of Le Mans-winning Commander Glen Kidston — a 1920s aviator and one of the original ‘Bentley Boys’ — and son of Commander Home Kidston, a pilot and gentleman driver, Simon Kidston has carved a reputation as one of the leading international dealers in blue-chip collector cars for the world’s elite, as well as a compere without compare, the brains behind the K500 index, and, above all, a true and discerning enthusiast. With the sumptuous and spacious interior of his beautifully restored Monteverdi 375/4 High Speed, illuminated by the glowing lights of London’s West End, serving as the perfect setting, this is our no-holds-barred discussion about the industry and how it’s changed, the current state of the market, and of course, how a junior at an auction house rose to become the face of the classic car world.

What are your earliest automotive memories?

Of going out on the family farm in our World War II Jeep with all the dogs — it wasn’t very fast, but it was noisy, muddy, and great fun. And of fast trips over the Alps in the back of our bronze BMW 3.0 Si in the 1970s, with Bert Kaempfert playing on the Blaupunkt stereo and my father driving with an ever-present cigarette. I’d always wondered what it would be like in a Lamborghini Countach from my Observer’s Book of Automobiles instead. My father also had a Signal Yellow Porsche Carrera RS, and I can still remember pedestrians turning to see what was coming when he put his foot down. It’s funny how you recognise the smell of cars — the RS brings back those memories when I open the door 43 years later. It’s fortunate that I kept it.

Did you always know you wanted to pursue a career involving cars?

Not at all. As a child, I thought London taxi drivers had the best job in the world, and maybe they do. Although, when I received my first bicycle, a career in Formula 1 usurped the taxi ambition. My family probably had other ideas: banking, property, or the services would have been considered more ‘proper’, but I’m still enjoying what I do too much to think about a grown-up career.

What happened?

My father gave me a small amount of money to buy my first car. He had a sensible used Renault 5 in mind, but I was thinking more about an Aston Martin. Actually, back then you could’ve owned an old DBS for about the same price. The only hiccup was the insurance for a 160mph cash-burner for a 17-year-old with a new license: I was quoted three times the cost of the car. It took me 20 more years to afford the Aston, but by studying Exchange & Mart and all the other car magazines, I learned a lot. Douglas Jamieson was then brave enough to give me a job at Coys of Kensington. I enjoyed it, worked hard, and because I spoke different languages, built up a strong European client base. Several years later, Brooks asked me to establish a new European division. They had Clapham in mind. I thought Geneva. Luckily Geneva prevailed.

What prompted you to establish your own business?

Because it was getting harder and harder to find good cars for auction, and I didn’t want to be promoting things that I didn’t love myself. The notion of pretending to be enthusiastic about something you don’t really love didn’t do it for me. The smart man is very disciplined and separates his hobby from his business, but I’m grateful that I can combine both. Any entrepreneur will also agree that sooner or later you have to run your own show. In my team’s case, it means we can devote the necessary time and effort to every project we undertake without big company restrictions. I’m lucky to have the best people in the field working closely with me.

How would you assess the collector car market right now?

It’s a very nuanced picture, and transactions require more patience and handholding than, say, five years ago. Looking back, 2007 was probably the market peak in terms of the speed at which deals were made, but values are much higher now and we’re doing strong business. The market has become much more polarised since the financial crisis of 2008 — the average value of the cars we’re selling has skyrocketed but the pace has slowed. If you’ve got the absolute best of anything, you can sell it. That doesn’t mean you can name any price, but if you’ve got something that’s demonstrably the absolute pinnacle, the negotiation is relatively straightforward.

Some are heralding the ‘return of the enthusiasts’ to the market. Do you think this is the case?

The fact of the matter is that enthusiasts spend less money. They might be nicer to deal with, but those who are buying for pleasure and not for profit simply don’t spend as much. We all like to think it would be idyllic if the market was populated with dyed-in-the-wool enthusiasts and not the new breed of ‘specollectors’, but cars wouldn’t be worth what they are now if people weren’t buying them to make a profit. Ultimately, this benefits everyone in the industry and the way cars are cared for. It’s an evolution we have to accept, although most of our clients still ask for cars they can drive and enjoy as their first criteria.

How do you interpret the sharp climb in demand for so-called ‘youngtimer’ Porsches?

For a certain generation, Porsche is a more accessible, aspirational brand than Ferrari, Lamborghini, or, say, Aston Martin. There’s a clear evolution in the demographic taking place, influencing what buyers want, but I think some people read too much into ‘outlier’ auction results. The auction houses are in the marketing business and serve a clear and useful purpose as clearing centres, but serious collectors need to be able to interpret the headline figures to understand how prices are developing over time and whether they’re comparing like-for-like cars. There are 1,400 ‘Gullwings’ in the world, for example. They might have all been created more or less equal, but the intervening 60 years have certainly taken their toll, and the survivors are chalk and cheese today. The same is true of Miuras, another of our specialities. ‘Youngtimer’ Porsches are easy to understand for relative market novices, and the entry ticket isn’t eye-watering. Beware, though: the gulf between the best and the rest in any field is widening, and it will continue to do so.

Throughout your time in the industry, particularly as a broker and consultant, where have you seen the biggest changes?

Ten years ago, the notion of buying cars as an investment didn’t have the same resonance as it does today. We all bought cars in the 1990s that increased in value in the 2000s, but the real acceleration had come in the last decade of low interest rates, particularly until 2014. That focused media attention on classic cars as investments like never before and provided the financial justification to buy more boldly and decisively. Traditionally, someone would have graduated to a ‘unicorn’ car, such as the Ferrari 250 GTO, through the middle tiers, but today’s über-collectors are on another level. Last year, we oversaw the sale of a GTO to a buyer who, a year earlier, had never owned a classic car. That’s a pretty steep learning curve. Wealthy newcomers entering the market tend to be very serious about it and far-sighted. They take a more scholarly view, seek advice on the key pillars of their collection, and retain an expert to find them.

Does the same principle apply for younger buyers?

It does. We handled four McLaren F1s in the last quarter of 2016. The strongest interest came from younger buyers, including a sports star. The youngest was in his twenties and the oldest in his fifties, which was unheard of until recently. One of the F1s we handled realised the highest price ever paid for any McLaren. It was more than any Ferrari 250 GT ‘SWB’ has ever made, including alloy-bodied competizione cars, and a figure that would have bought a 250 GTO a few years ago. Tastes are clearly changing, and this generation does its homework with methodical dedication.

Has being an F1 owner helped you to sell such a great number of these cars?

I’d be lying if I said it’s hurt, but I didn’t buy the car for that reason — I bought it because I always remembered the day, around 1994, when the McLaren salesman came to the mews where I worked and I asked if he’d take my colleague Vanessa and I for a drive around the block in Kensington. I couldn’t believe how angrily this thing took off down Gloucester Road, or the expression of the Irish builders on the nearby scaffolding.

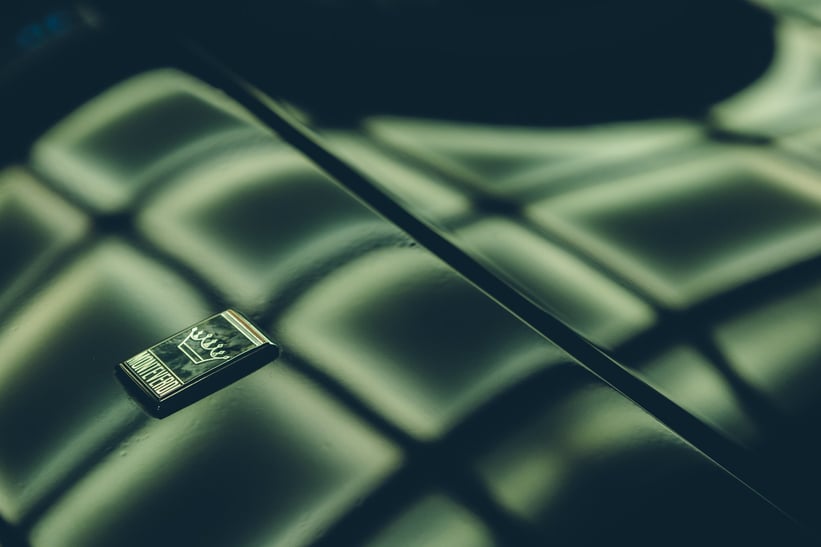

Was buying a Monteverdi a case of Swiss national pride?

No, I’ve always had a thing for fast saloons — I grew up sitting in the back of them, and my first company car was a second-hand Mercedes-Benz 500 E, which I absolutely loved. The Monteverdi was something that always fascinated me, because it was elegantly good looking, unfeasibly powerful, had 1960s ‘GT man’ styling, and almost nobody knew what it was. I bought it from collector Bruce Milner in the States, after meeting him coincidentally in a lay-by outside Los Angeles while spectating at a small local car get-together.

And what’s this particular car’s history?

Bruce bought it from a Scot who’d been an engineer in Qatar, where he’d acquired it in a scruffy state a few years earlier. It was built for the Qatari royal family, who probably sold or gave it to a local mechanic when it outlived its usefulness. Monteverdis are mysterious cars worthy of any iffy spy movie from the late 1960s, and their former head of sales, Paul Berger, has been very helpful with research. I’ve continued restoration where Bruce left off, and for the past two years, Mototechnique has been fine-tuning it for proper driving. We even tracked down the period-correct Sony television for the rear cabin, which was a special order on the car when new. Sadly, not many stations broadcast a 1977 signal!

Is it important for you to attend so many events across the world?

I don’t go to as many as I can, rather the ones that matter, because you learn things all the time. Some of them I’ll do purely because they’re fun, like the Ollon-Villars Hillclimb, but others are more business-centric. No offence to Scottsdale in Arizona, but it’s not a place car-minded people usually visit to admire the desert or cacti — you attend the auctions, read the signals, and listen to what’s really going on and who’s buying or selling. You don’t learn this in the office.

You must love compering at events such as Villa d’Este and the Mille Miglia, though?

Yes, I do, but I’m trying to be very disciplined in choosing which to do. You don’t want to be omnipresent, and there are other people who do a great job. I’ve stopped commentating at the Mille Miglia, at least for now. It was great fun but chaotic, and there was always a power struggle between the different organisers. It’s a buzz to be up on the ramp in Brescia waving people off, but it’s a bit like watching other people have sex — you really want to be doing it yourself.

Have you taken part in the event as a participant?

I started doing the event myself and commentating, which was quite difficult. I had to leave last from each stop, which meant I was driving like a mad man from the very beginning, trying to catch up. Fortunately, I was driving a Jaguar D-type, so it didn’t take too long. I did quite a lot of the Mille from the passenger seat in 2015 — it’s so cramped, hot, and noisy, but actually, after half an hour you’re anaesthetised and your brain stops worrying about it. It’s a priceless experience.

Do you think a victory in events such as the Mille Miglia and at Goodwood enhance a car’s value?

Not for a ‘major-league’ car. It helps somebody’s kudos as a driver, but you don’t really want to have an important car that’s constantly winning historic races, because it implies that it’s had so many parts modified to be competitive that it can’t be original. The most valuable cars rarely come out to race anymore, sadly. Where once you might have seen four Ferrari 250 GTOs battling wheel-to-wheel, nowadays it's more likely to be ‘bitsa’ Cobras versus E-types built yesterday. But that’s a whole other debate.

What would be in your dream three-car garage?

I’ll never be able to afford my perfect three-car garage. No matter how much you earn, you’re always at least one step — in my case, many steps — behind it. But the dream would be a Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, a Ferrari 250 LM, and a Bugatti Royale. The latter might seem like a strange choice today, but I’ve always loved their mystique and colourful histories. I’ve sold several 250 LMs in my career and it’s always been my favourite Ferrari. And the SLR? The holy grail, which Mercedes-Benz kindly lent to me for a 60km test drive. Being deaf never felt so good.

Finally, do you track your air miles?

No, I don’t really want to know!

Photos: Alex Lawrence / The Whitewall for Classic Driver © 2017