When millions of euros’ worth of collector cars slid across the frozen lake in St. Moritz at ‘The ICE’ winter concours back in March, there was one guest that caught our attention. The modest but creatively customised Mercedes-Benz W123 estate, with its elegant dark blue paint and yellow-tinted fog lights, casually mixed with blue-chip Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Lancia rally cars and caused quite the stir on our Instagram channel.

Its owner is Michele Lupi, a multitalented Milanese journalist who started the Italian editions of Rolling Stone, GQ and Icon before being appointed as the first ‘Men’s Collections Visionary’ at Tod’s. When we met Michele again at a pop-up exhibition he’d curated for Tod’s during Milan Design Week in the spring, he invited us to return to the city to visit his favourite spots and talk cars and design. Naturally, we accepted his invitation.

The car park where Michele keeps his car and where we agreed to meet this morning is Autorimessa Cesena, one of the city’s typical hidden historical locations that you’d never stumble upon – unless you know where to look, that it. The modernist two-storey building was built in 1950 on a football pitch once used by Inter Milan for training. Having been owned and run by the same family for three generations, the car park – with its large glass façade, crumbling green paint and almost tropical fauna – is a time capsule that allows you to breathe the pioneering spirit of post-War Milan.

Just as we start admiring the owner’s Alfa Romeo 1750 Berlina, we hear the characteristic horn of a classic Mercedes. Michele has arrived and being the fast-paced thinker and storyteller that he is, we immediately engage in conversation.

You grew up in the heart of Milan in the 1960s – could you tell us about your family and the city back then?

I was born in Milan in 1965 and while most bourgeois families were moving away from the city at that time, we stayed right in the centre. The area was run down, dangerous even, but fascinating. My family was rather unconventional because my father was an architect and graphic designer. He worked with Archille Castiglioni and created the logos for Fiorucci, Miu Miu and the bicycle brand Cinelli. He was also Art Director for Domus and Abitare magazines. Both my parents were fascinated by Anglo-Saxon culture and we had a house near Kew Gardens in London for some years, which we often visited. As a child, I was always exposed to art, international style, graphic design and architecture. I was breathing it all in.

From where does your fascination for cars stem?

Nobody has a real passion for cars in my family. But one Christmas, my mother went to the Triumph dealer, bought a white Spitfire with a cream-coloured roof and part exchanged my father’s Renault 4 without him knowing. She gave the new car to him as a present and he was desperate! He loved his Renault as it was a perfect architect’s car, but the Triumph was kept and driven all around Europe with me squeezed between the seats. I guess that’s when I got interested in cars.

A car is a fascinating object – essentially, it’s a small house you can heat up and drive around. And the windscreen is like a cinema, through which you can always see something different. Later, I studied architecture like my father, but I didn’t finish because I wanted to write about racing cars.

Why racing cars?

When I was 11, I was sent to a Polish private school in South Kensington for English lessons. One of the boys in my class was Giuseppe Cipriani, whose father had founded Harry’s Bar in Venice. He later became a professional racing driver and Formula 3000 team owner, but even back then he was really passionate about racing. One day in 1976, he asked me if I’d like to go to Brands Hatch to watch the Formula 1. The race was a tough fight between James Hunt and Niki Lauda. The crowd was cheering, the noise of the Cosworth and Ferrari engines was astonishing and I completely fell in love with motorsport. I went home that night with the noise still ringing in my ears.

Is there a Formula 1 race that you particularly remember?

Later that year, I was sleeping at a friend’s house and we woke up at five in the morning to watch the Japanese Grand Prix. Everybody else in the house was asleep and it was very cold, but I couldn’t take my eyes away from the black-and-white television. The race was delayed again and again because of the rain, but then they decided to ahead. Niki Lauda retired and James Hunt won the championship by just one point. Many years later, the famous Scuderia Ferrari engineer Mauro Forghieri told me that they left Fuji in a Rolls-Royce with Niki Lauda while the race was still on. They were listening to the Japanese coverage on the radio, with the co-driver translating the outcome of the race just as they arrived at the airport.

How did you get into journalism and writing about cars and motorsport?

One Christmas, my father designed and printed a personalised stationary set for me, including letterheads and business cards. One design was inspired by the seven-day travelcard for the London Underground. When I decided I wanted to write about cars when I was a student, I wrote letters to different publishing houses in Milan. I never received an answer, until someone from Rizzoli called me to say they weren’t interested in my writing but asked who designed my stationary. I told them the story and invited them for a drink. We got on well, so I started moving their test cars for my first job and also wrote some short pieces. Later, I moved from cars to other fields of journalism and was a travel correspondent in New York, before I founded the Italian editions of Rolling Stone, GQ and Icon.

We leave the car park and drive towards Lupi’s favourite workshop. Lounging in the leather seats of the roomy Mercedes while navigating through the city’s morning traffic towards an industrial area in Lambrate, we want to learn more about the car.

Could you tell us about your Mercedes?

It’s a 1982 Mercedes-Benz 280 TE. I’m not too interested in the rarity or value of a car, but more the design and the details. I’m particularly interested in estates and shooting brakes. Before this car, I owned a Mercedes 300 diesel which was in very good condition but had no air-conditioning. During the summer, it was simply too hot.

The burgundy leather is from German Auto Tops in Los Angeles that specialises in vintage Mercedes leather. I had it shipped and fitted here. I also switched the standard steering wheel for a Nardi one as in the 1980s in Italy, all the T models had the Nardi wheel. It might not be all original, but I prefer to have a car that I like. I also added the yellow fog lights and the Norton stickers. I simply love classic racing stickers and tee-shirts from the 1950s and ’60s, perhaps because of my father’s work. I’ve always had a soft spot for old logos and graphic design.

What do you find so appealing about estate cars?

In 1982, I spent some time in London with two friends. One night, we had to decide whether we wanted to watch the football World Cup final between Italy and Germany in a pub or The Clash live in Brixton. I ended up going to the concert alone and waited in front of the backstage door for the band to arrive. Suddenly, a bright red Ford Granada estate pulled up and all four members of The Clash climbed out. Later that night Italy won the World Cup, but I was certain I’d made the right decision. There’s something about estate cars from the 1980s that always reminds me of that night.

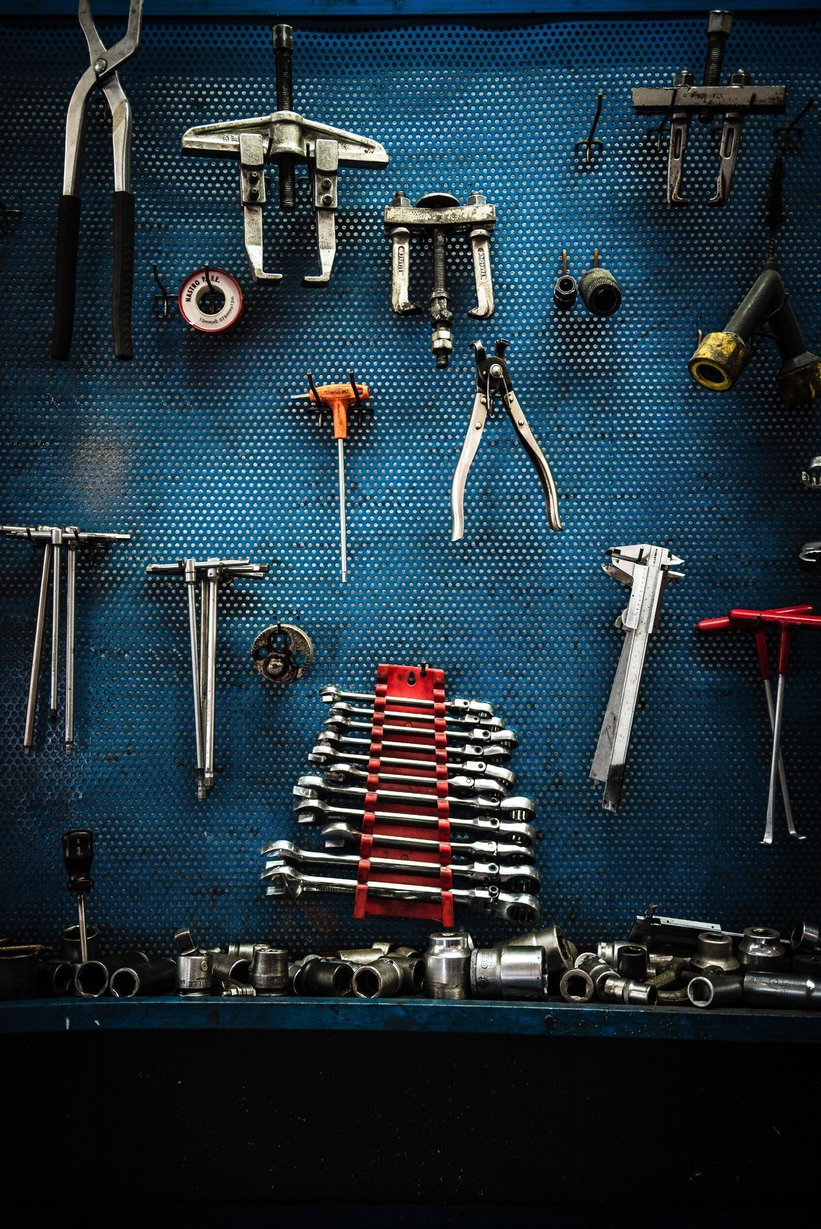

After navigating through a labyrinth of brick warehouses, a line of classic Mercedes’ in various states of disrepair indicate that we’re getting closer to our destination. Ricky Motors is run by Enrico Pighetti, the former chief mechanic of Mercedes-Benz Milan. And according to Michele, it’s the go-to place for passionate collectors of 1980s and ’90s Mercedes-Benzes in Northern Italy. Pighetti doesn’t focus exclusively on classic cars, however – he is a true 360-degree mechanic. “I don’t care about the value of a car and it doesn’t make any difference whether I get my hands on a Fiat 850, a Ferrari 250 GTO or a Suzuki Ignis,” he explains. “What interests me and gives me the most satisfaction is working on an engine and solving any problems.”

Michele, how long have you had your cars serviced by Ricky Motors?

The first time I visited Enrico was around nine years ago. I had a high-mileage Porsche 993 Carrera 4, which I used every day. I regularly took it to Porsche for maintenance and, inevitably, ended up spending a lot of money. Then someone told me to go to Enrico. When I visited him, I met the two Porsche mechanics who usually looked after my car. They wanted Enrico’s advice on a mechanical issue that was too problematic for them to solve. I introduced myself and he was immediately very kind and welcoming. Above all, I was struck by his curiosity – not for cars, but for people. He was an authentic person, someone in which you can instantly sense their good and clear soul. I had found the mechanic and friend I’d been looking for for my entire life.

We bid farewell to Enrico, who immediately dives into another engine bay, and head to our lunch spot, the excellent seafood restaurant I Sapori del Mare on Via Goldoni. Over branzino to die for and excellent white wine, we finally find time to ask Michele about his new job at Tod’s – and the secret of Milan’s elegance.

What exactly does the role of ‘Men’s Collections Visionary’ entail?

The idea for the role came from Diego Della Valle, the fashion entrepreneur and owner of Tod’s who hired me. He said, “let’s do something romantic!” and, of course, I couldn’t resist. He’s always hungry to do something different and keep the creativity of his brand alive. For the Tod’s No_Code exhibition I curated for Milan Design Week this year, we created a setup of temporary housing structures designed by Andrea Caputo and interviewed entrepreneurs, designers and creative thinkers. Among them was Marcello Gandini, Chris Bangle and Mai Ikuzawa. It was quite experimental for Tod’s, but the show was praised by visitors and the press. After working as a journalist all my life, it’s something altogether new.

Milan has become Europe’s creative hotspot – how has the city changed since the days of your youth and what is the secret behind Milan’s attraction?

Milan has always been a cultural centre in Europe. The Expo certainly played an important role in the recent revolution of Milan, but I think the new quarters at Porta Nuova and the Fondazione Prada were a gift to the city. Then there is the certain attention for style and aesthetics which is specifically Milanese. It’s a strange city – it’s grey, not too big and not as beautiful as Rome, Florence or Venice. But still, it has this silent elegance and the 1950s and ’60s are very present in the architecture. During Salone del Mobile, architects, designers and students from all over the world come here for an incredible week in the spring when the city explodes with creativity. At the same time, Milan is a city that likes to keep its secrets hidden. Most of the time you only see a layer and a façade. But if you explore further and dig deeper, you often enter another hidden world that nobody knows about – just like this restaurant, my car park and Enrico’s workshop. There’s always something new to discover.

Photos: Andrea Klainguti for Classic Driver © 2019